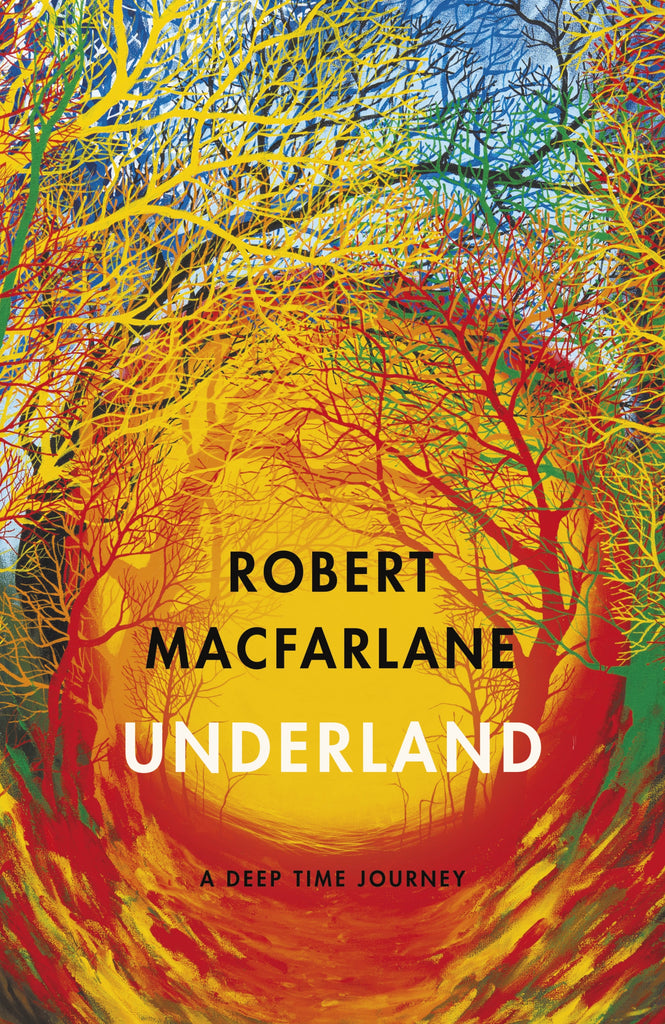

Underland by Robert Macfarlane

Nature writer Robert Macfarlane has always been drawn to “up in the air” places, said Adam Nicolson in The Spectator: the Cambridge don’s previous books – “on climbing, walking, being in remote places” – have been a “sequence of the high and the wide”. In Underland, by contrast, he moves his focus downwards, to the “under-geography of the world”. From such dark and airless spaces as the caves of the Mendips, the Parisian catacombs and a nuclear-waste storage facility in Finland, Macfarlane sends back a series of haunting dispatches, imbued with “anxiety” and a sense of “lostness” while also “filled with diverting facts”. Such spaces, Macfarlane points out, have long exerted a powerful metaphorical pull, appealing to our sense that what is hidden is more important than anything “easily to hand”. But they’re also of great practical use: they’re the places where we hide precious objects, where we dig for what is valuable and where we dispose of what might be harmful. A work of huge ambition, Underland is a “stirring response to the strange landscapes hidden beneath us”, and is by some distance Macfarlane’s “most powerful book”.

I’m not so sure, said John Carey in The Sunday Times. Macfarlane is justifiably loved for being able to “convey the sights and sounds of the natural world”. Yet by venturing down into caves and tunnels, he has robbed himself of this ability. “It is like a romantic poet deciding to wear a blindfold.” But given its subject matter, it is hardly surprising that this book is “darker” than anything Macfarlane has written before, said William Dalrymple in The Guardian. And in any case, the “melancholic” tone fits with a growing awareness of humanity’s desecration of the planet. By concentrating on the rocks beneath us, he has found a way to write about our “almost incidental place in the world when seen from the perspective of geological time”. This is, unquestionably, his “magnum opus”.

It’s not a book I was disposed to like, said David Aaronovitch in The Times. On the basis of what I knew of its author, I suspected a lot of it would be “artful communing-with-myself-in-nature mysticism”. And in fact, I wasn’t entirely wrong: by chapter four, Macfarlane is already “wandering the greensward” accompanied by a mycologist (fungal expert) called Merlin. But despite the outbreaks of self-indulgent lyricism, and Macfarlane’s tendency to take himself (and other people) too seriously, I ended up being won over. “Cave by cave, subterranean river by hidden tunnel, buried isotope by melting ice floe, he got to me.”