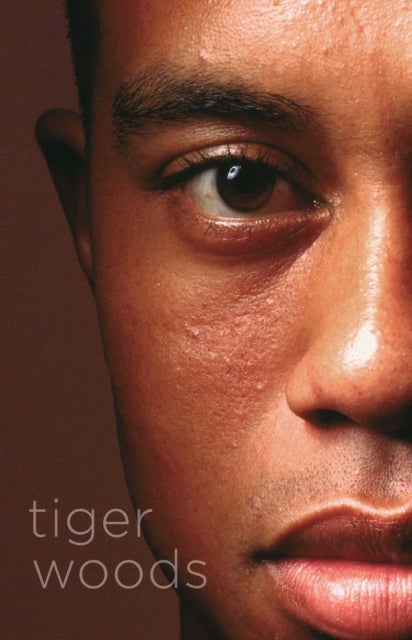

Tiger Woods by Jeff Benedict and Armen Keteyian

Tiger Woods was always destined to be a great golfer, said Giles Smith in The Times. His father, Earl, a Vietnam veteran and an instructor in “military science and tactics”, drilled him from a very early age (an approach he dubbed “the Woods Finishing School”). When Tiger was a baby, his high chair was moved to the garage so he could “watch golf balls being hit into a net”. From the time he could wield a golf club, he was forced to practise two hours a day and Earl would tape motivational messages to his bedroom wall: “I believe in me”; “I am first in my resolve”. All this enabled Woods to bypass the “traditional, white, moneyed” route to golfing success and become the sport’s first black superstar, amassing 14 majors, 79 PGA Tour events and £110m in prize money. Yet while his golf “spoke magnificently for itself”, the man who played it remained “bafflingly remote”. As the authors of this “unstinting” biography put it, he was “invisible in plain sight”.

In 2009, the world finally discovered why, said Dwight Garner in The New York Times. On the day after Thanksgiving, high on sleeping pills, Woods “groggily” crashed his SUV into a fire hydrant outside his home while trying to flee his wife, who had “learnt of his adultery”. In fact, as became clear, she “didn’t know the half of it: Woods’s paramours (strippers, waitresses, neighbours) began popping up from behind every swizzle stick”. Since then, the “greatest athlete of our time” hasn’t won a single major tournament, and his injury-racked career has nosedived badly (though just recently, it has shown signs of reviving). Based on 250 interviews, this confident biography brings “grainy new detail” to almost every aspect of its subject’s life.

Woods, it transpires, wasn’t just a sex addict and a liar, he was also “a horrible human being”, said Jim White in The Mail on Sunday: “spoilt, entitled, utterly self-obsessed”. But he has never been stupid. So why did he jeopardise his “carefully honed image” by indulging in “absurdly risky behaviour” – not just the relentless womanising, but also a series of secret parachute jumps that badly damaged his back. Benedict and Keteyian offer an “intriguing” answer: Woods, they suggest, “needed the impetus of his double life to stimulate his golf”. The theory certainly explains why, ever since his comeback – after therapy, which allowed him to understand “how vile he had been to those close to him” – his performances have been so mediocre. It seems that “the more human he becomes, the less effective Tiger Woods is as a golfer”.